A Board (bored) Walk?

Is anyone else out there just plain bored with the goings on in the world - the world we’ve built? Bored with their job? With the monotony of the everyday? With the dulling thrum of institutionalized life and the parade of media-fed memes and soundbites so short they barely qualify as thought?

We’re living in an age of overstimulation and under-saturation—where attention is a commodity[1], curated experiences replace real ones, and the soul of things is bought, sold, and speculated on like stock in a fading empire. For many, life has become a kind of obligatory performance—a rote and mind-numbing series of tasks, where questions of purpose and possibility are filed away under “impractical.” But perhaps the more impertinent question is not whether we’re bored—but why we’ve stopped questioning at all.

Walk the halls of our universities and you’ll find bright minds bound to a single script: get into a good school, get a good job, get a good life. But tucked neatly within that storybook arc lies a deeper, unspoken plotline—money. Not openly declared, of course—we are far too polite for that—but it’s the gravitational center of our entire educational galaxy. The hidden curriculum is economic. The politics are clear. The avenues are marked. The ends are presumed noble.

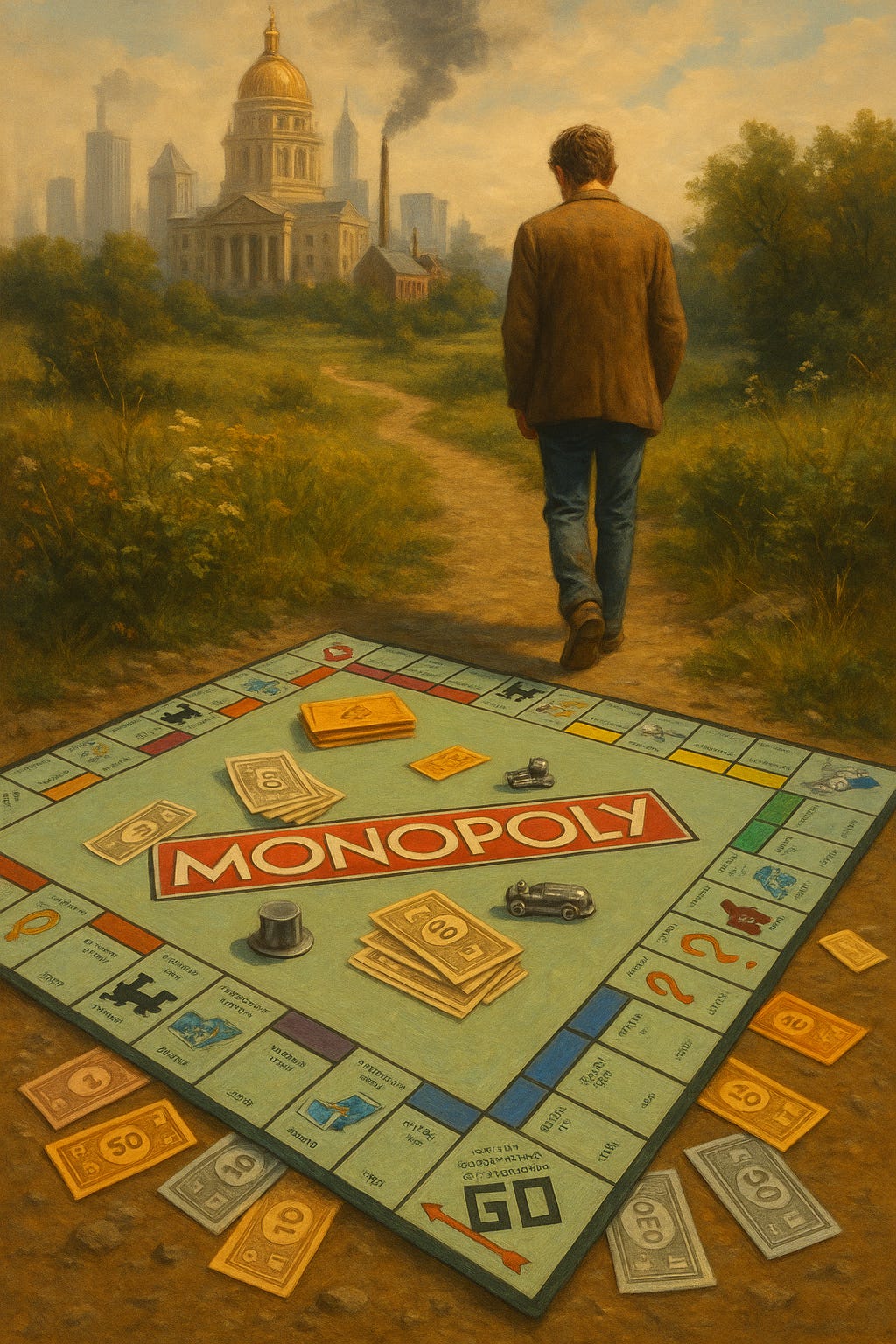

And isn’t it, after all, a kind of Monopoly?

We all know the game. Roll the dice, collect $200, travel around a square board of acquisition and defeat. Buy and sell, trade and tax, bankrupt your opponents, and become the “monarch of the world.” It’s a game built on the premise that wealth equals victory and that dominance is the natural outcome of success. Not the expressly stated aim of academia today, perhaps—but how far off is it really?

Competition within higher education is intense. Stakes are high, and the debt accrued in pursuit of this supposed “good life” now dwarfs the opportunity it once promised. The playing field? Hardly level. And like Monopoly, the rewards concentrate in fewer hands while most circle the board endlessly, hoping for luck or to stay solvent.

Education was once thought to be the great equalizer—a ladder toward upward mobility. But Thomas Merton, with his usual unflinching clarity, called this promise into question. “The mass production of people literally unfit for anything except to take part in an elaborate and completely artificial charade,” he wrote. It’s a system that too often functions like a factory, stamping out students into roles crafted by a marketplace hungry for compliant, debt-laden participants.

During the original Great Depression, a laid-off radiator repairman invented a game to mirror the capitalist system. It caught on quickly, providing entertainment to the down-and-out. Monopoly offered more than amusement—it promised fantasy riches and control at a time when both were in short supply. Parker Brothers made billions on the illusion of hope, and players—desperate for control in a chaotic world—kept rolling the dice. In some ways, we haven’t stopped. Monopoly has become the metaphor for our times, and many of our educational institutions seem to serve as training grounds for this game of accumulation and domination.

Mark Zuckerberg, Time magazine’s 2010 Person of the Year, didn’t need to graduate from Harvard to strike it rich. Facebook was his railroad and utility, Boardwalk and Park Place, all rolled into one. He is now among the reigning royalty of our digital Gilded Age—alongside the likes of Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos. These men didn’t just win the game; they rewrote its rules. Bezos, once an ambitious bookseller, now commands a planetary empire of labor and logistics, private space programs, and untraceable wealth. His personal net worth has exceeded $235 billion, while his warehouses are monitored to the second, and his employees have been known to relieve themselves in bottles to meet their metrics. This is the New Monopoly: played in real-time, with global stakes and very real consequences.

And yet, for many, the dream of “Easy Street” still lingers—fueled by cultural myths and institutional endorsements. The Monopoly board’s Free Parking square, where players sometimes stash windfalls of cash, mirrors our contemporary belief in unearned rewards: the free rider syndrome. It’s the hope that prosperity will find us by simply being present, that benefits can be enjoyed without contribution. And so, we wait—for the promotion, the lottery win, the passive income. All while the planet buckles under the weight of our expectations.

But history tells us such gilded fantasies don’t last. The original Gilded Age—named by Mark Twain in his satirical novel The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today—was characterized by extreme inequality, monopoly capitalism, political corruption, and the rise of robber barons. The wealth was dazzling on the surface but rotten at the core. Beneath the gold leaf lay poverty, labor exploitation, child workhouses, and a nation on the verge of revolt. That era collapsed into the Progressive movement of the early 20th century, fueled by labor unrest, muckraking journalism, and public outcry. Trusts were broken up. Antitrust laws were passed. Income taxes were introduced. Even capitalism’s most ardent defenders recognized that unregulated greed was unsustainable. It is worth remembering that the Gilded Age did not end because the wealthy grew compassionate—it ended because people fought back.

Today, echoes of that gilded collapse are once again reverberating. Just as before, the surface gleams—record stock prices, tech breakthroughs, billion-dollar startups—but beneath it festers a climate crisis, housing insecurity, rampant mental illness, and educational disenchantment. The air is thick with déjà vu.

Environmental scholars and thinkers have long pointed to this crisis of meaning. David W. Orr, professor and ecological visionary, insists that what is wrong with the world is not simply the lack of education, but the wrong kind of it. Our current models, he writes, “alienate us from life in the name of human domination, fragment instead of unify, overemphasize success and careers, separate feeling from intellect and the practical from the theoretical, and unleash on the world minds ignorant of their ignorance.” It is a staggering indictment. Yet it rings true. We are schooled for success, not for survival, trained for profit, not for purpose. We graduate fluent in the grammar of economics, yet illiterate in the language of the land.

Gary Snyder sharpens the blade further. The problem, he says, is not the unschooled, but the hyper-schooled—the impeccably groomed professionals with credentials and charisma, reading refined literature while orchestrating policies and investments that unravel the Earth. These are not the unwashed masses. They are graduates of the finest institutions. They dine on local-organic cuisine while making global decisions that strip-mine cultures and ecosystems alike. It is a troubling contradiction—and a call to conscience.

Thoreau, as always, speaks with prophetic resonance. In Life Without Principle, he asks us to consider how we spend our lives—not just our income. “The ways by which you may get money almost without exception lead downward,” he warns. “To have done anything by which you earned money merely is to have been truly idle or worse.” He challenges us to build our houses—and our lives—upon “foundations of granite truth,” not the rotten sills of easy wealth or superficial success. Thoreau feared the trivialization of the mind—that our very thoughts might be “tinged with triviality” by constant exposure to the inconsequential. The dangers weren’t just financial—they were spiritual and intellectual.

He chose to finish his education at a different school from the one offered by Concord’s town center. And so should we.

The way forward may not be through another career pivot or institutional reform alone, but through a radical reimagining of what it means to be educated. To learn not merely to earn, but to discern—to grow in awareness, responsibility, humility, and care. To feel again the rhythms of a world not organized by time clocks and market indices, but by moonrise and soil and birdsong.

Einstein reminds us that “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” And perhaps we cannot solve our deepest problems by simply playing a better game of Monopoly. The answer may lie not in winning, but in walking away.

Walking—as Thoreau knew—is not simply locomotion. It is liberation. “I have met with but one or two persons in the course of my life,” he wrote, “who understood the art of Walking.” It is a refusal to go in circles, a reclamation of agency, a slowing down in a world obsessed with speed. To walk is to remember what it means to be human and to encounter again the land not as a commodity but as kin.

So forget the Boardwalk. It’s boring. Take a walk through the fields, the woods, and the neighborhood gardens that remain unpaved. Step off the circuit. Leave behind the colored spaces and the fake money and the frantic march toward accumulation. Take a path that leads away from Easy Street, away from the engineered promises of Free Parking. You may find yourself bored at first. But boredom, real boredom, is fertile ground for reflection, insight, and change.

Let your feet wander. Let your thoughts deepen. Let your questions grow larger and less answerable. And in time, you’ll begin to glimpse a different kind of wealth—a wild, abundant, soul-filling wealth that cannot be bought, hoarded, or measured, but only lived.

That is the walk worth taking. That is the real education.

[1] A good read is Chris Hayes’ “The Sirens’ Call”; Penguin Press, 2025