Crossing the Threshold

Why Rites of Passage Matter More Than Ever

There was a time when every human life was marked by thresholds—moments of passage when the old life was left behind, and a new one began. To be born, to reach maturity, to marry, to die—each was framed by ritual, by shared meaning, by the attentive presence of the tribe. These rites of passage were not mere ceremonies but vital crossings: they affirmed the unity of the individual and the community, the body and the soul, the human and the sacred. Today, in a culture that hurries through its stages and flattens its mysteries, these passages have all but vanished. We have graduations, promotions, birthdays, and retirements, but few authentic initiations—few moments that transform. The result, as the psychologist Marie-Louise von Franz observed, is a civilization of “half-grown” adults—souls who have aged but not matured, who move quickly but have never truly crossed.

The anthropologist Arnold van Gennep first gave this human pattern its name. In his 1908 book Les Rites de Passage, translated into English in 1960, he described how every culture marks transitions through a tripartite pattern of separation, initiation, and return. The initiate is separated from the familiar world, undergoes a period of ordeal or transformation, and then returns—renewed, humbled, and integrated into the community’s life. These rituals, van Gennep saw, were not peripheral to human life; they were its scaffolding. Adolescence, in particular, was the time when this scaffolding mattered most —the period when a young person’s energy—the ancient Litima, as one text calls it—boils and strains for form. It is a time of intensification, a time when identity is forged in the crucible of change. Without guidance, that fire can turn destructive; with it, the youth becomes a source of light and renewal for the tribe.

The need for such transformation is inscribed in the psyche itself. Carl Jung called adolescence the hour of the soul’s first encounter with its own shadow—the moment when one becomes aware of inner contradiction and conflict, when the protective myths of childhood dissolve. He warned that if these energies are not contained by ritual, they often erupt in compulsions—addiction, violence, self-obsession. Michael Meade, in his introduction to Crossroads: The Quest for Contemporary Rites of Passage, tells the story of the “Half Boy,” a youth who has not yet been initiated, who remains split between worlds. Only through ordeal, Meade writes, can the half-boy become whole—through facing trials that awaken self-knowledge, through symbol and story that bind him to the deeper patterns of life. Without such passages, we remain only partially alive, wandering through adulthood without ever having been born into it.

Rites of passage, in this sense, are crucibles of change. They do not merely celebrate growth—they cause it to happen. They create the psychological heat in which the elements of the self are melted, separated, and re-formed. They are the soul’s alchemy. Mircea Eliade, in The Encyclopedia of Religion, defined rites of passage as rituals marking a person’s passage through life’s stages, “leaving behind the attitudes, attachments, and patterns of the previous stage.” Margaret Mead went further, warning that when a culture loses its rites, it suffers an increase in pathology. In the absence of meaningful initiation, she wrote, youth invent their own trials—drugs, speed, gangs, and reckless acts of self-destruction—all unconscious attempts to break through the membrane of childhood. The person with an addiction, Jung saw, is a failed initiate—someone seeking transcendence without transformation.

If we listen closely, we can hear the same cry everywhere in our culture today: the yearning for ordeal, for meaning, for a passage into maturity that the culture no longer provides. Adolescence has become a perpetual state; adulthood, an illusion. The “village” that once celebrated and absorbed the initiate has dissolved into a network of screens, algorithms, and markets that feed upon youthful uncertainty rather than guide it. Our culture prizes perpetual youth, not wisdom; speed, not stillness. Yet, as Crossroads reminds us, “to remember ritual, we must slow down.” The machine age has taken its toll not only on the environment but on attention itself. Indigenous peoples, who had no machines between them and their gods, understood that life must be approached slowly and reverently. They built their rituals around the rhythms of Nature: sunrise and sunset, seasons and solstices, silence and sound. The walk itself was a prayer, a passage.

To create sacred space, the elders would set apart a time and a place beyond the ordinary. The young would enter that space—sometimes a forest, sometimes a desert, sometimes a sweat lodge or a mountain cave—and there undergo the trial that would change them. It was not cruelty, but care, that shaped these rituals; the community knew that the soul’s maturity could not be bestowed, only earned. One must be “baked in the oven,” as a Buddhist teaching puts it, until one’s whole being is cooked, matured, transformed. The Buddhist monastic initiation, similar to the vision quest or the walkabout, required the novice to face solitude and fear, shifting their identity from the “body of fear” to the “body of knowing.” What emerged was not mere self-esteem but self-respect—a calm heart, a fearless spirit, an awakened compassion. “On this earth,” the Buddha said, “the only true nobility is the nobility of heart and spirit that a human being brings to their life.”

Such awakenings have always required mentors—elders who themselves have walked the path. In Homer’s Odyssey, the goddess Athena guides Odysseus through his long trials, appearing often in disguise, even to his son Telemachus, as “Mentes”—a word meaning “teacher.” From that name, we derive our word “mentor.” The ancient story reveals a truth that modern psychology has only rediscovered: we cannot initiate ourselves. The elder’s task is not to impose wisdom but to help the initiate discover their own. In Crossroads, Mead insists that instead of giving youth answers, we must provide them with questions—questions that awaken their own authority, helping them discover their own values. To find one’s true power, one must first learn to use it wisely.

But what happens when there are no elders, when the marketplace has replaced the village? Robert Bly called our era “the Age of Endarkenment,” not because there is no light, but because we have lost the art of tending it. The intensity of adolescence, which once found expression through ritual, now finds it in addiction, distraction, and despair. The “skills and experiences necessary to enter adulthood,” Bly and Meade remind us, were once learned through practice, through genuine encounters with the world. Now we send our youth into a digital labyrinth, where stories are consumed rather than lived. The LongWalk has become the long scroll. Yet the need remains unchanged: the adolescent must still cross the threshold and discover their inner strength and purpose. If denied the craving, we do not eliminate it—we distort it. “Deny the craving, don’t meet the need,” as one line from Crossroads puts it.

There is an ancient word for the energy that courses through the adolescent soul: Litima—the inner heat. It is the willful, emotional force that fuels the process of becoming. In healthy cultures, this fire is channeled through the rites of passage, where individuals are indulged, exposed, educated, and sanctified. When no channel exists, the fire rages unchecked, turning creative power into destruction. To harness this energy is to forge the future of the culture itself. The adolescent’s trial, properly guided, is the culture’s renewal. Eric Erikson, in mapping the stages of human development, identified adolescence as the stage of identity formation—the time when one must answer the question, “Who am I?” But identity cannot be conferred by consumer choice or social media profile; it must be discovered through encounter—through challenge, reflection, and solitude.

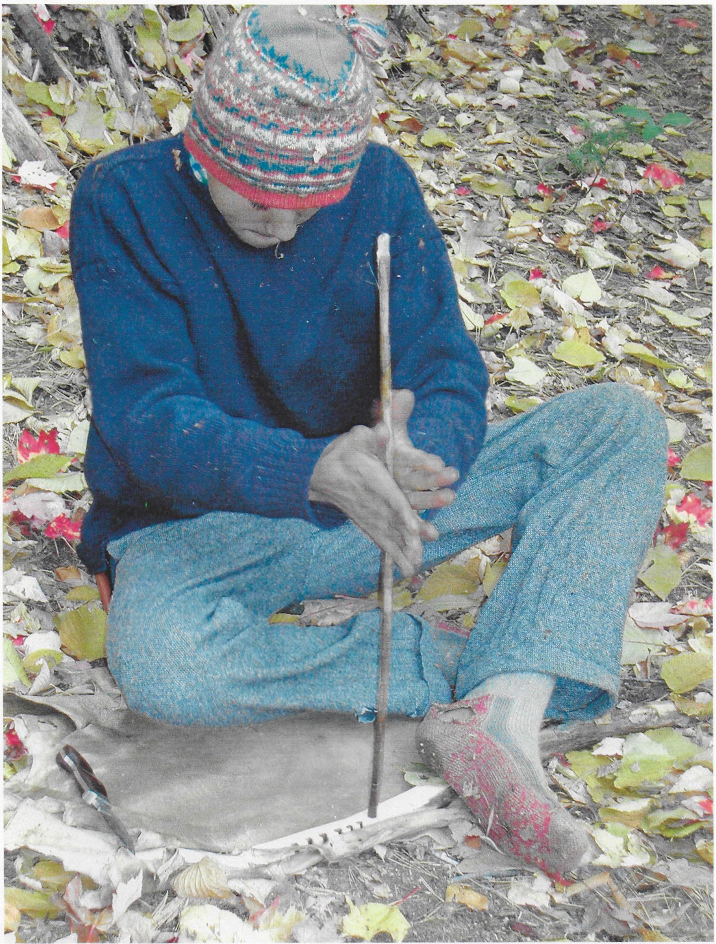

At this point in American life, the rite of passage, as one writer in Crossroads notes, “is a concept in search of a reality.” We sense its absence but have forgotten its form. Yet our ancestors knew that inner change often requires outer change—a shift in setting to evoke a shift in soul. Thus, vision quests, pilgrimages, and wilderness journeys served as thresholds. In each, the initiate left the known world behind to face the elemental forces: hunger, fear, silence, and beauty. The wilderness was not an escape but a mirror, reflecting the inner terrain. In the wild, we learn to see again, to hear the questions that civilization drowns out: What calls me to the adventure of my life? What am I willing to risk for it? What must I leave behind?

These questions lie at the heart of every mythic journey. In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell traced the universal pattern of initiation through the world’s myths: the call to adventure, the crossing of the threshold, the ordeal, the revelation, and the return. Star Wars, with its hero Luke Skywalker leaving home to face the unknown, remains perhaps our most accessible modern retelling of this pattern. The hero’s path, Campbell wrote, is not the acquisition of power but the discovery of self-knowledge—the movement from innocence to awareness. To embark on this path requires imagination, for imagination is “the thought of the heart.” It is through image, symbol, and story that the heart comes to know itself. Rites of passage, in this sense, are more art than science. They must both preserve and create; they must be recreated in each generation.

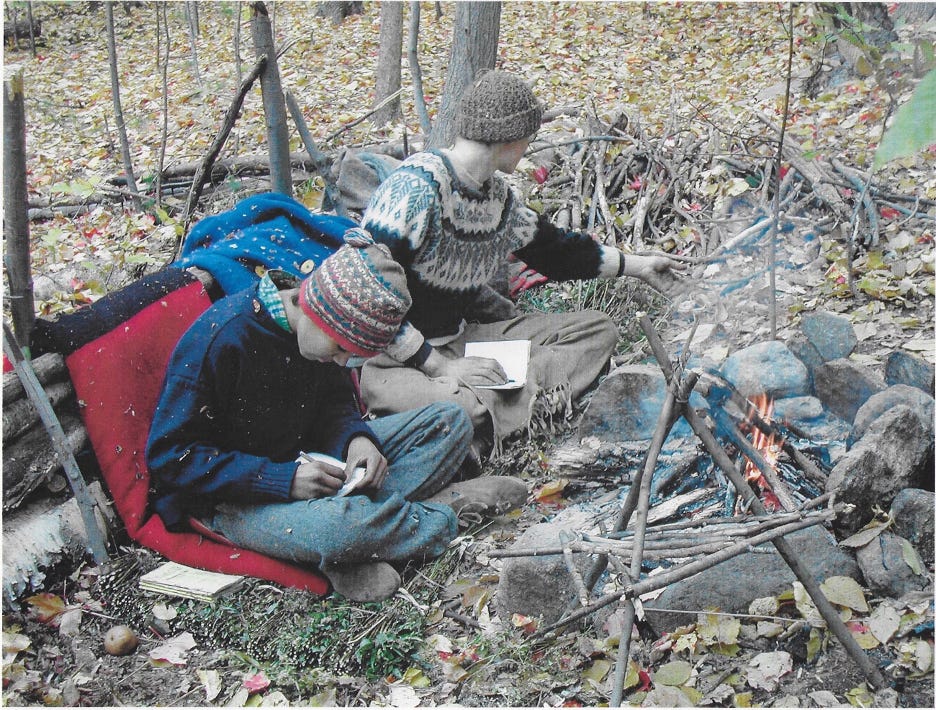

If imagination is the thought of the heart, then stories are its grammar. Myths, dreams, and legends are not mere fictions; they are the maps by which the soul navigates the invisible terrain of change. The Australian Aboriginal Songlines, for instance, trace not only geography but cosmology—songs that mark the land and the self simultaneously. To walk them is to remember who you are. Such stories, rooted in the land, offer an antidote to our present disconnection. In a globalized world where synthetic images and virtual narratives bombard young people, what is most needed are stories that reconnect them to place, purpose, and one another. The journal, as Crossroads suggests, becomes a contemporary tool of initiation—a place where the youth can record their journey, turning experience into meaning.

The first crisis of adolescence is separation—leaving the familiar world. The second is entering the new one. In between lies the threshold, where solitude and vision are necessary. Yet, modern culture offers few spaces for solitude and few opportunities for the young to hear the call of their own lives. Our days are filled with noise; our nights, with light. The “pollution of the mind” is now as real as that of the air or sea. Without silence, there can be no listening; without stillness, no transformation. To restore rites of passage, we must reclaim these silences—the wildernesses within and without where the soul can breathe.

An actual rite of passage does more than elevate the individual; it renews the community. Traditional initiations returned the youth not as conquerors but as contributors—as men and women entrusted with the well-being of the tribe. In our culture, where adulthood is often defined only by economic independence, this social dimension has been lost. As Crossroads observes, when young people are denied meaningful roles in the community, self-destructive behaviors take their place. Work, stripped of purpose, becomes drudgery; education, detached from wisdom, becomes rote training. What is needed is not more schooling but more initiation—learning that connects inner growth to outer service, personal meaning to collective responsibility.

To rediscover ritual, we must slow down; to slow down, we must walk. Walking, as Thoreau and so many others have observed, is the original rite of passage, the act of leaving the village and entering the wilderness, of moving between worlds. The pilgrim’s path, the monk’s procession, the scout’s trail—all mark the body’s participation in spiritual change. Each step becomes an act of attention. In the speed of modern life, this may be the most radical act we can perform: to stroll, to listen, to remember that the world itself is sacred space.

Ultimately, the task is not to recreate old forms of ritual, but to restore the old depth of attention. Rituals are living things; they must be rooted in the present while drawing nourishment from the past. To initiate the young today means helping them discover meaning in a world that often seems devoid of it—to cultivate inner strength, a sense of purpose, and a capacity for solitude. It means guiding them to the edge of their own experience and allowing them to cross.

Perhaps the new rites of passage will not take place in temples or forests but in classrooms that honor imagination, in journeys that reconnect us to the land, in communal practices that awaken reverence and responsibility. What matters is not the form but the function: the awakening of the heart, the discovery of self, the return to community.

We live in an age that prizes distraction and fears silence, that confuses information with wisdom and connection with communion. Yet beneath the noise, the ancient need persists. Every youth still carries within them the call to adventure, the longing to be initiated into the mystery of their own life. Every culture must find ways to meet that call or risk losing its soul. To create new rites of passage is, finally, to remember what it means to be human—to mark time not by consumption but by consciousness, not by achievement but by awakening.

As the elders once knew, the passage from innocence to self-knowledge is the passage by which life renews itself. The task before us is to restore the sacred art of crossing—to guide the half-boy and half-girl within each of us toward wholeness, toward wisdom, toward the nobility of heart that alone can sustain a culture. For if we do not teach our young how to cross the threshold, they will remain forever waiting at its edge—burning with the fire of Litima, yet never transformed by it. To create rites of passage is to make meaning itself, to offer the next generation what every soul requires: a place to stand, a story to live, and a path that leads, at last, from the half-life of the uninitiated to the fullness of being fully alive.