The Handmade Path

Education, Masculinity, and the Lost Art of Adventure

The first spark came slow, coaxed by friction and breath. Kneeling in the damp leaf litter, I cupped my hands around the faint curl of smoke rising from the bow-drill set I’d made earlier that morning—cedar spindle, birch hearth, braided 4-ply linen cord. Around me, nine others worked in quiet concentration, each absorbed in the ancient struggle to summon fire from nothing but patience and intention. It was late autumn. The air had that particular kind of chill that wakes every sense, a thin clarity that makes even failure feel instructive.

We were ten in all—students, teacher, wanderers—each answering a restless call we could no longer ignore. We had grown weary of mediated lives, of an education that spoke to the mind but not to the body, and of a culture that measures growth in productivity rather than presence. What we were seeking wasn’t novelty; it was something older, more honest—an education of the hands and the heart.

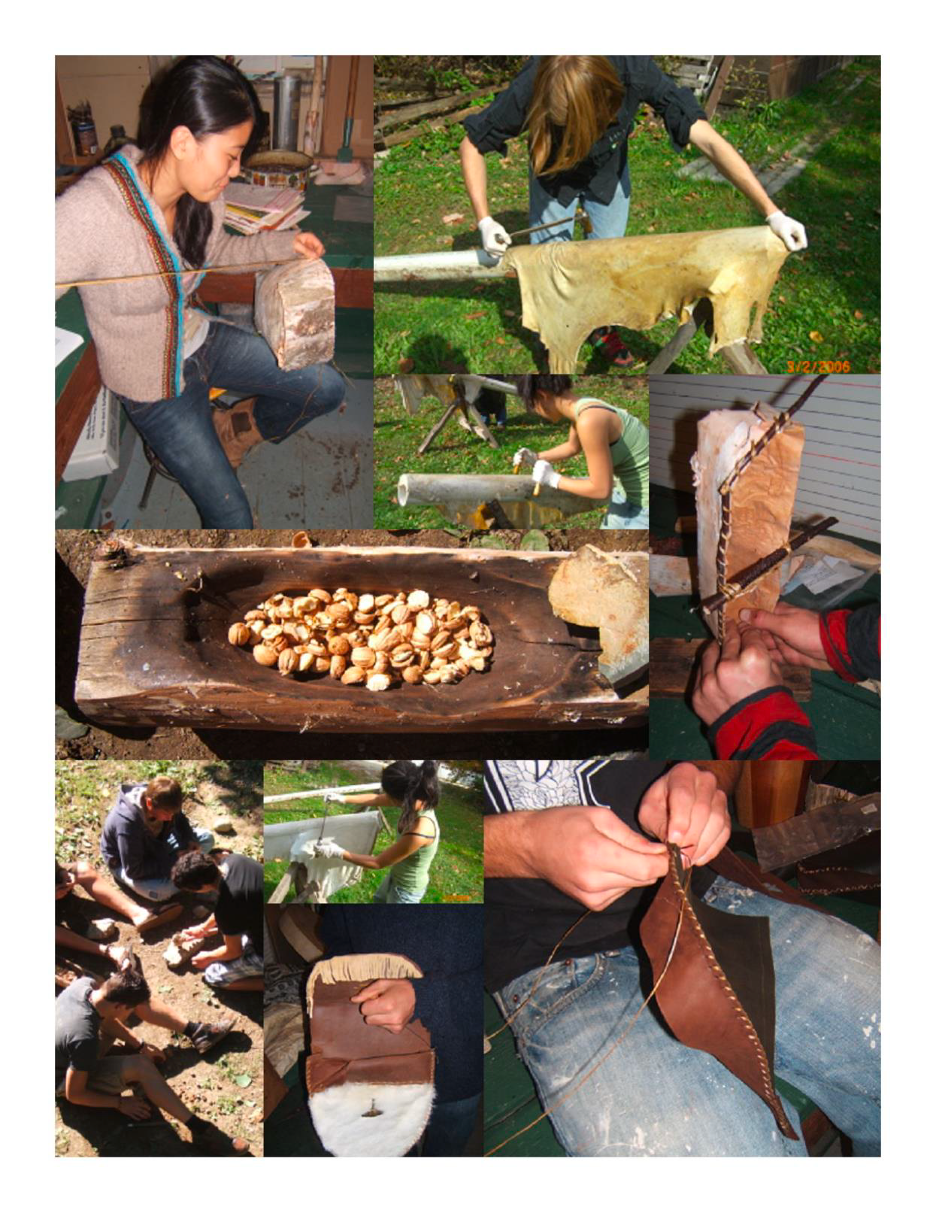

In the months leading up to that weekend, we studied the old ways. We learned to twist cordage from plant fibers, to tan hides, to carve tools from bone and stone. We stitched our own bags, shaped our own containers, wore clothing of our own making. We discovered what earlier peoples had taken for granted: that to make something is to know oneself through the resistance, the temperament, the living conversation of material. Birch bark, for example, behaves like a sentient thing—pliant when coaxed, brittle when hurried. Every craft demanded attention not for the sake of technique alone but because the process itself reoriented us toward presence.

This was not extracurricular. It was education—an education we have systematically erased from our schools. The hand has been divorced from the head, and both have been estranged from the heart. Yet as we shaped these simple tools, we were shaping an awareness of belonging, rediscovering that learning once emerged from the same soil as survival. And it was here, amidst the bark shavings and quiet camaraderie, that I began to understand just how profoundly Ernest Thompson Seton had grasped the essential role of the natural world in forming a whole human being. Seton knew that the work of the hand was inseparable from the work of the soul.

Across cultures, the passage from childhood to adulthood has always been marked by trial and transformation. From the Maasai warrior’s solitary hunt to the Native American vision quest, societies found ways to test the emerging self against the natural world. But we have abandoned that tradition. We’ve traded ordeal for comfort, initiation for consumption. Adolescents today—saturated in technology, buffered from risk—are denied the very experiences that once taught resilience, empathy, humility.

When Baden-Powell founded the Boy Scouts in 1908, he believed he was addressing this very loss. But the deeper root system of the movement belonged to Seton—artist, naturalist, storyteller—whose “Woodcraft” offered not merely an outdoor program but a philosophy of becoming. Seton understood what educators and parents still hesitate to name: that a young person’s character is shaped most powerfully through a relationship with the living world. Nature is not a backdrop but an instructor; stories are not entertainment but initiation. Seton’s pedagogy was an ecology of attention—a way of cultivating presence, humility, and moral imagination. For him, the forest was the first and most essential classroom.

And while his work drew inspiration from Indigenous models—where learning emerges through imitation, story, and direct encounter—Seton resisted the extractive tendencies of his era. He urged educators and parents alike to recognize that children do not grow through lecture but through lived reciprocity with the land. The power of a tracking story, the silence required to observe a fox, the humility awakened by carving a flawed spoon—these were not sentimental adornments to education but its very essence.

In Finland, they still know this. Their education system remains rooted in what Uno Cygnaeus envisioned when he introduced Sloyd—a handcraft-centered curriculum meant not to create artisans but humans. Finnish schools integrate woodworking, textiles, outdoor exploration, and thematic, nature-based learning not as electives but as pillars of human development. Children there grow up stitching, carving, skiing, wandering forests, studying weather and ecology as living subjects rather than test content. Their thematic approach allows knowledge to grow interconnectedly, organically, like the ecosystems it describes. It is the closest contemporary expression of Seton’s vision—a system where the child is not a data point but a participant in a living world.

This is not nostalgia; it is pedagogy. And it stands in contrast to the American model, where education has grown abstract, industrial, and digitally saturated—a system that asks students to absorb information but rarely to inhabit knowledge. It is a system that leaves parents anxious, teachers exhausted, and students hollowed by attention fatigue. Families sense that something essential is missing, but lack a language to articulate it. Seton gives us that language: learning must be lived in the body, grounded in place, nourished by story, and shaped by responsibility to something beyond the self.

Why has American education forgotten the body, the land, the senses—and the character-shaping encounter with something larger than oneself? In our race toward technological mastery, we have neglected the more profound mastery of self. Our devices give us access to everything except intimacy. They offer immediacy without embodiment, information without transformation. We scroll through adventure rather than live it.

As we prepared for our weekend in the woods, I was struck by how foreign even the simplest acts of self-sufficiency had become. Making a birch container or striking fire without a lighter felt, to some, like rebellion. And in a way, it was—a rebellion not against modernity, but against passivity. Each time we replaced convenience with creativity, dependency with discovery, we reclaimed a small portion of agency that our culture has quietly eroded, especially for young men. Here, too, Seton’s insight radiated: that boys, in particular, hunger not for dominance but for meaningful responsibility, for tasks that require attentiveness, courage, subtlety.

Much of contemporary masculinity is performance—a brittle reaction to a world in which genuine initiation has vanished. Without rites of passage rooted in community and nature, young men reach for extremes: aggression without purpose, risk without guidance, identity without grounding. Primitive skills—when practiced with humility and camaraderie—offer another path. They transform strength into stewardship. They reveal that masculinity need not be loud or defensive; it can be attentive, patient, skillful, protective of life rather than domineering over it. Seton understood this intuitively. His camps, stories, and ceremonies offered boys and girls alike a way to inhabit courage without violence, competence without ego, and belonging without subjugation.

Around the fire, masculinity softened into something truer. There was laughter, exhaustion, and silence. No one needed to posture or compete. We were simply human—capable, vulnerable, alive.

The night we built our shelter, the temperature fell below freezing. We worked quickly, cutting fallen boughs, weaving walls, and sealing gaps with debris. The structure was crude but dependable, and as the fire crackled at its entrance, we felt a comfort no mattress or thermostat could replicate. Shelter, we realized, is not merely an object but a relationship—with material, with weather, with one another.

Reading the land, sensing weather, adapting to cold—these were not survival skills so much as acts of reconnection. In learning to live with the natural world, we were learning to live with ourselves. And this, too, was Seton’s quiet thesis: that ecological literacy and self-knowledge are not separate pursuits but entwined ways of being. Later that night, lying awake beneath woven branches, I understood what this education offered: the rare experience of being fully present. A friend once told me that happiness emerges when we stop wishing we were elsewhere. In the forest, that truth felt embodied. This moment is enough.

Primitive skills do not come naturally to everyone. But something in us remembers. To strike fire from wood or cook over coals awakens an ancestral memory, a reconnection to a lineage of survival and meaning that predates all our abstractions. In a society suffering from ecological dislocation and psychological drift, these acts become medicine.

Adventure, I’ve come to believe, is food for the soul—not the hyper-packaged adventure marketed to us, but the raw, unpolished kind that demands our presence. To endure discomfort is to rediscover vitality; to create with our hands is to reclaim our place in the broader fabric of life. Modern education, in its fixation on metrics and screens, often forgets this. It treats knowledge as accumulation rather than transformation. But when we work with wood, hide, stone—when we learn directly from weather and forest—we are shaped in return. We learn patience from bark, humility from fire, and adaptability from cold.

When we returned from the woods, nothing outward had changed, yet everything inward had. We no longer looked at tools, clothing, or food the same way. We saw the hidden chain of dependency behind every object—the ecological and human labor masked by modern convenience. Making things had not taught us merely how to survive, but how to perceive.

We came home with calloused hands and clearer minds. The noise of modern life felt newly abrasive, its speed and superficiality almost comic. But I did not wish to reject it. Instead, I felt compelled to bridge the two worlds—to carry that quiet, grounded attention back into daily life. There is a wisdom in the old ways that modernity still needs—not nostalgia but nourishment. We need an education that engages the whole person; one that asks not merely what do you know? But who are you becoming?

When I think back to that first flame—the moment smoke turned to fire—I see more than a spark. I see the possibility of an education that heals. I know what Seton understood so clearly: that humans are transformed not by information but by encounter. I know a masculinity capable of tending rather than taking. I see humanity still able to regain its balance, if only we allow nature to teach us again.

Through the handmade path, we remember that education is not preparation for life; it is life itself. And life, when lived with our hands, our senses, and our full attention, becomes an adventure worthy of the human spirit.

Beautiful, profound as always. I so enjoy reading your essays. They bring me tears of joy and hope in my heart. My finances are very low, but perhaps in the future I will be able to pleine. Blessings for the new year.